February on Hothfields: A spotlight on reed mace

Long-time volunteer Margery Thomas explores the wildlife at Hothfield Heathlands in February, where reedmace tells a story...

Figure 1. Coastal chalk erosion including cliff, cave, stack, arch and chalk reef platform. Whiteness, Broadstairs.

The area is cared for by a management group which consists of representatives of relevant organisations that have regulatory authority within the site. Support is provided by an army of enthusiastic volunteers from the Thanet Coast Project, Kent Wildlife Trust and Natural England who donate hundreds of hours and boundless energy onsite throughout the year helping to maintain and protect the designated inter-tidal features.

However, having such an impressive degree of protection does not make the location immune from threats which affect its favourable condition. Two such threats are currently subjects of investigation:

The Invasive Non-Native Species project was launched by Natural England in 2007 initially targeting the Pacific Oyster Magallana gigas, which is native to north-east Asia and has been trans-located around the world to support the shellfish industry. In 1964 they were introduced to the United Kingdom by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries to offset the decline of the Native Oyster Ostrea edulis. Due to low sea temperatures, they were not expected to reproduce in United Kingdom waters. However, in 1994 wild settlement was recorded at locations in Devon where oysters had spread from nearby aquaculture sites.

The 2007 baseline survey showed that wild Pacific oysters were present across the expanse of the NEKMPA inter-tidal zone. Settlement was greatest along north Kent sections peaking at Epple Bay, Birchington, where native habitats had been converted to an oyster reef. Peak density here reached 212 live oysters/m². Figure 2 (below) shows oyster reef formation at Epple Bay.

Figure 2. Inter-tidal mussel bed converted to oyster reef. Epple Bay, Birchington.

The native species most affected was the Common Mussel Mytilus edulis. Ross Worm Sabellaria spinulosa and Sand Mason Worm Lanice conchilega populations were also recorded at risk. In 2011 the survey was repeated with Natural England including 5 additional species:

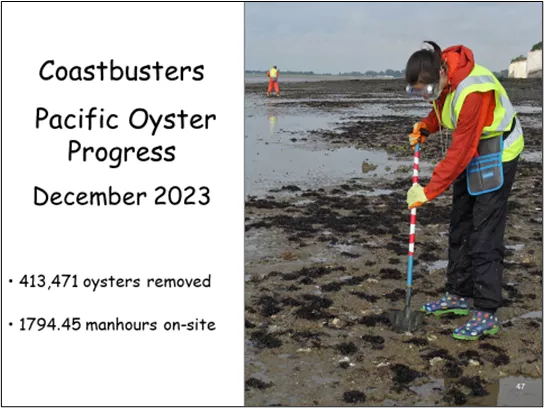

The Pacific oyster ranked as the species posing the greatest threat based on an impact score generated for each species. In response a team of volunteers was set up to test the feasibility of controlling oyster spread at selected sections based on best practices identified by Natural England. Since its launch in 2012, the “Coastbusters” team has been active within selected sections of the NEKMPA. The National Nature Reserve at Sandwich & Pegwell Bay is seen as a priority and to date the team has been successful in preventing habitat modification of the mussel bed, chalk reef and extensive mudflats. Figure 3 (below) shows control results so far.

Figure 3. Coastbusters results July 2012 – December 2023.

Inter-tidal mussel beds are important habitats providing shelter and food for many marine species. They are included in the UK Bio-diversity Action Plan as a priority habitat. Within the NEKMPA inter-tidal mussel beds are populated by the Common Mussel Mytilus edulis. Such sites are classified as Features of Conservation Interest (FOCI) and are required to be maintained in favourable condition. Pacific oyster larvae settle on mussel shells to the extent that established mussel bed habitats are modified to become oyster reefs resulting in the decline of some species associated with mussels. Figure 4 (below) shows a juvenile oyster attached to a mussel shell.

Figure 4. Juvenile Pacific oyster attached to the shell of a Common Mussel.

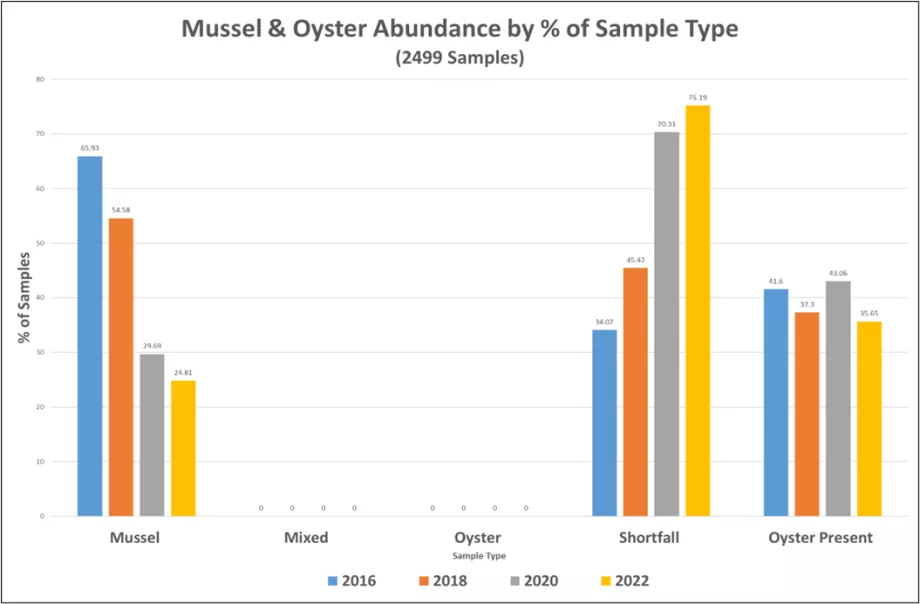

The invasive non-native species project confirmed the threat posed by the spread of wild Pacific oysters to inter-tidal mussel beds and highlighted the need for a standard, evidence based, process to assess their long-term condition. In 2016 a process was developed and field tested at the inter-tidal mussel bed within the Sandwich & Pegwell Bay National Nature Reserve. The process was repeated in 2018, 2020 and 2022 enabling the management group to assess the ongoing condition of the site in terms of encroachment by wild Pacific oysters. Over the six-year study period a baseline and trend were established. Results showed oysters present across the expanse of the 5.4ha site. Oyster numbers varied slightly between survey periods suggesting the population is stable. Local factors such as the volunteer control effort and the presence of oyster-herpes virus, Os-1μv, may be contributing to this stability. Figure 5 (below) shows 1m² sample results (2499 samples) over the study period.

Figure 5. Results by 1m² Sample Type and Oyster Present. (Shortfall: mussel/oyster cover is < 50% of sample area).

An unexpected finding was the alarming decline of the mussel population which appears to be unconnected with the spread of oysters. This can be seen in Figures 6.1 and 6.2 (below) looking east at Western Undercliff in Ramsgate.

Similar observations have been reported at other mussel beds in Kent and beyond. Further research is needed to understand the cause and consequences of this decline. The Common Mussel is a cold water species so maybe climate change is a factor?

Both projects are ongoing reporting to the North East Kent Scientific Coastal Advisory Group and Natural England who work in conjunction with other conservation and marine organisations including Kent Wildlife Trust, The Environment Agency, Kent & Essex Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority, Medway Swale Estuary Partnership and Thanet Coast Project to care for and maintain the Kent coast in favourable condition.

Long-time volunteer Margery Thomas explores the wildlife at Hothfield Heathlands in February, where reedmace tells a story...

If December was a merry berry month for humans celebrating mid-winter festivities, January and February are serious berry months for birds and mammals aiming to survive winter...

In our December instalment about Hothfield we focus on mosses and lichens on the reserve. Read on to find out more.