Background

Wilder Blean is a wilding project at West Blean and Thornden Woods, near Canterbury, Kent, UK. The surrounding Blean woodland complex is one of the largest surviving blocks of ancient semi-natural woodland in England. Wilder Blean currently covers an area of 562 hectares, comprising a mosaic of ancient oak-hornbeam woodland, mixed broad-leaved coppice with standards, extensive stands of sweet chestnut coppice, conifer plantations, and small areas of heath, wetlands as well as several man-made ponds.

The wider Blean landscape is a stronghold for Heath Fritillary Melitaea athalia, a butterfly species not threatened globally, but classified as Endangered in Great Britain following a 90% fall in its population since 1980 (Lofting, 2024). Approximately, 60% of UK colonies are found in the Blean, owing to monitoring and management efforts. Common Cow-wheat Melampyrum pratense and Ribwort Plantain Plantago lanceolata are two key food plants for the adult butterflies. Populations of these plant species have been encouraged in the Blean through regular coppicing, however, this management approach is unsustainable. Our long-term hypothesis is that livestock and bison activity will reduce woody plant cover, leading to an increase in the abundance of these food plants.

Large grazing herbivores, including European Bison Bison bonasus, Exmoor Ponies Equus ferus caballus, British Longhorn Cattle Bos primigenius, and Ironage Pigs Sus scrofa × Sus domesticus, were introduced at Wilder Blean in 2022. This is a trial with the aim of improving the condition of the nationally important Site of Special Scientific Interest, some of which is in unfavourable condition (Natural England, 2025).

Large grazing herbivores went extinct in the UK, and across much of Europe during the late Holocene at the end of the last Ice Age, due to a combination of human activity and environmental changes. This was detrimental to the ecosystems in which they evolved, as the functions they provided were lost and natural processes they facilitated were disrupted. Large herbivores control plant growth, maintaining habitat mosaics which support more species, and they disperse seeds that they consume. They create microhabitats by disturbing the ground through trampling, dust bathing or wallowing. They recycle nutrients from plants back into the soils through their dung. They are prey for large predators and scavengers, and support birds and invertebrates that use them as hosts, their dung for food, or their fur for nesting materials. They sequester carbon into soils through their dung and by encouraging new rapid plant growth (Borer and Risch, 2024).

At Wilder Blean, the large herbivores have been reintroduced, but their dispersal is limited by fences. The fences are arranged to provide a robust experimental design, comprising three different treatments. The ‘Bison treatment’ contains European Bison only. The ‘Conservation Grazers treatment’ contains conventional conservation livestock including Longhorn Cattle, Exmoor Ponies and Iron-age pigs. The ‘Control treatment’ contains no introduced grazing animals and is managed by a human workforce, including coppicing, for example. Due to the delayed construction of the bison tunnels, which allow the animals to travel under public rights of way and disperse across the site, the bison treatment has been limited to only one of five parcels in the southeast of the site.

This design enables a comparison of the effects of European bison, livestock commonly used for conservation purposes, and traditional human management on the ecosystem, to generate evidence on the effectiveness of European bison as a conservation management tool.

This report summarises the results of the Heath Fritillary food plant surveys conducted between 2021 and 2024.

Methodology

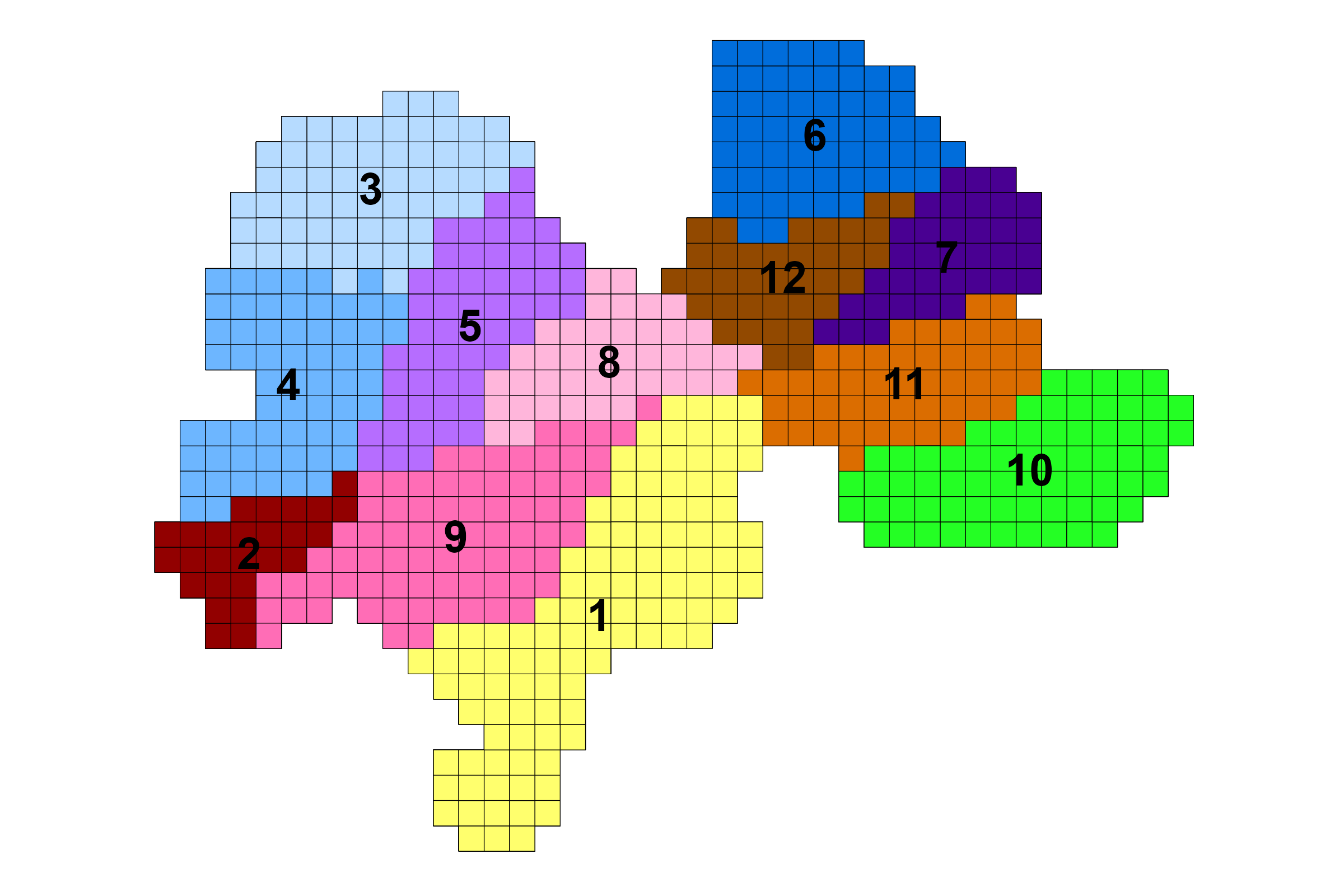

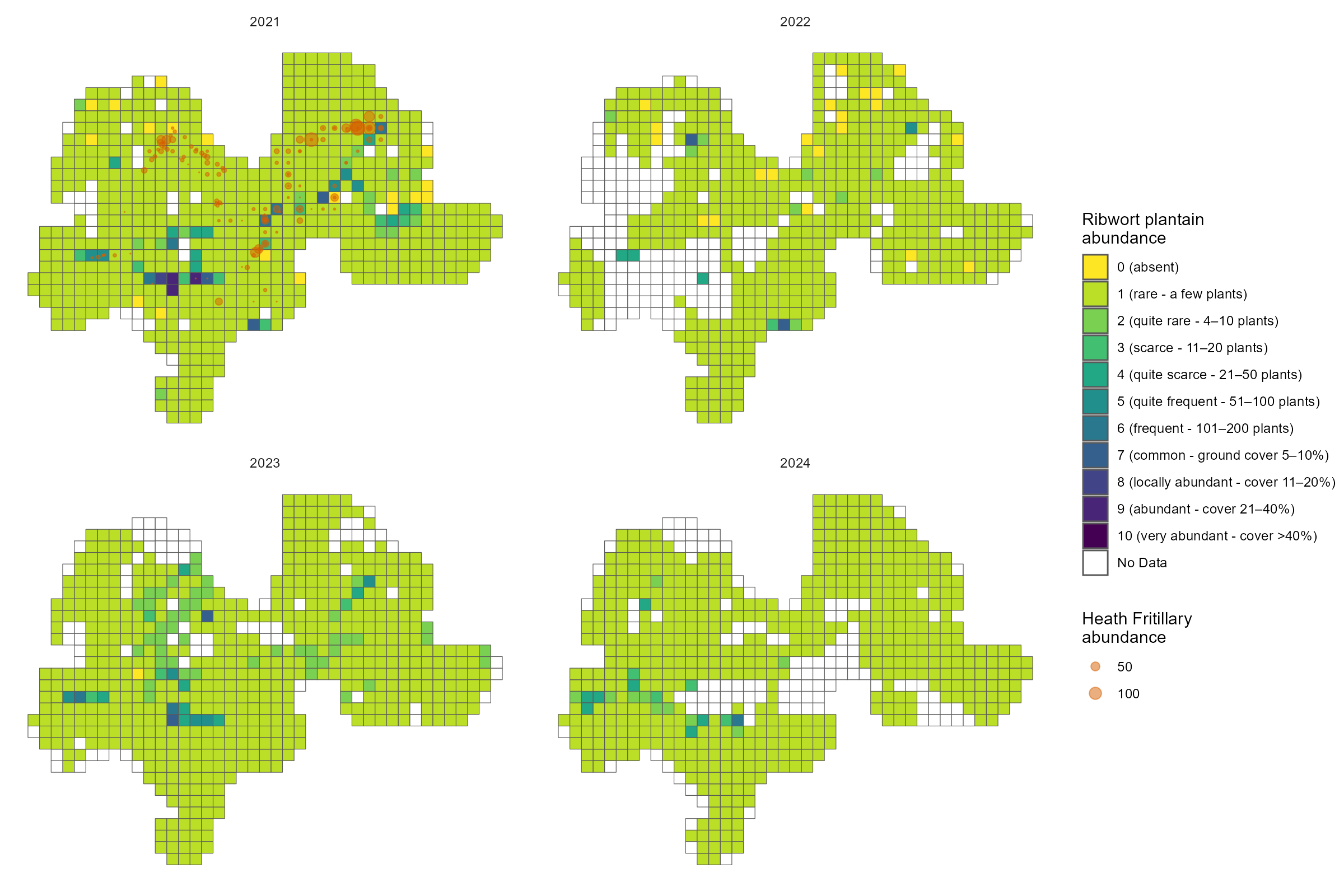

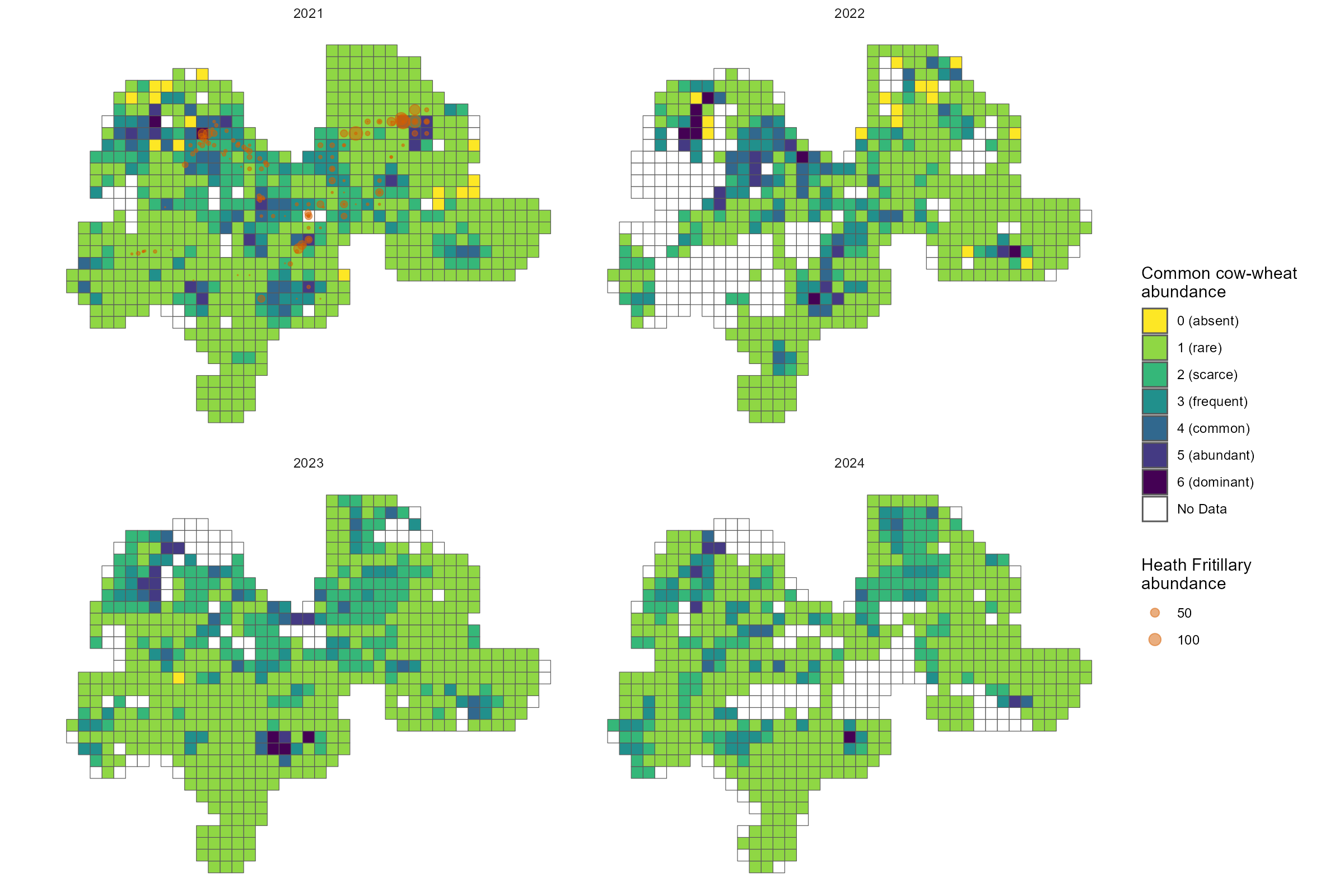

Surveys of the Heath Fritillary food plants, RIbwort plantain Plantago lanceolata and Common Cow-wheat Melampyrum pratense, were conducted at 673 square plots covering the entire project area (Figure 1). The plots measure 100 x 100 m. In each plot the abundance of each food plant species was assessed. The abundance of Common cow-wheat was measured on a 6-point scale from absent to dominant. The abundance of Ribwort Plantain was measured on a 10-point scale from absent to very abundant. Due to resource constraints complete coverage was not possible in all years.

Two Cumulative Link Mixed Model (CLMM) were used to analyse change in the abundance of each food plant species across years, while accounting for the repeated measures within survey areas. CLMM provide a robust method for analyzing ordered categorical data within a repeated measures framework. Plant abundance, measured on an ordinal scale from 0 to 10, was treated as the ordered response variable. The primary predictor was 'year' (2021-2024), and 'survey area' was included as a random effect. The random effect acknowledges the non-independence of observations collected within the same geographic areas over time. The clmm model estimates the log-odds of Ribwort Plantain or Common Cow-wheat being in a higher abundance category between years.

Results

The results of the CLMM revealed significant changes in Ribwort Plantain abundance relative to the 2021 baseline. Specifically, the log-odds of being in a higher abundance category in 2022 were significantly lower than in 2021 (Estimate = -0.9486, SE = 0.2569, z = -3.692, p < 0.001). Conversely, 2023 showed a significant increase in the log-odds of higher abundance compared to 2021 (Estimate = 0.5297, SE = 0.1966, z = 2.694, p = 0.007). However, no statistically significant change was detected in 2024 when compared to 2021 (Estimate = -0.2245, SE = 0.2222, z = -1.011, p = 0.312). These results indicate notable fluctuations in Ribwort Plantain abundance over the study period, with significant shifts in 2022 and 2023, but no statistically significant change in the overall population trend over the three-year period. Model diagnostics indicated successful convergence and significant variability in baseline abundance across the 12 survey areas.

The results of the CLMM revealed no statistically significant changes in Common Cow-wheat abundance over the 2021-24 period. The log-odds estimates were close to zero for all years, with corresponding high p-values (2022: estimate = -0.0002, SE = 0.1297, z = -0.002, p = 0.999; 2023: estimate = 0.0463, SE = 0.1185, z = 0.390, p = 0.696; 202: estimate = -0.1780, SE = 0.1243, z = -1.432, p = 0.152). Model diagnostics indicated successful convergence and significant variability in baseline abundance across the 12 survey areas.

Discussion

We assessed the initial effects of introduced large grazing herbivores, including European bison, on the abundance of two key Heath Fritillary food plants, Ribwort Plantain and Common Cow-wheat, at Wilder Blean. Our long-term hypothesis is that livestock and bison activity will reduce woody plant cover, leading to an increase in the abundance of these specific food plants.

The findings for Ribwort Plantain revealed statistically significant fluctuations in abundance, with a notable decrease evident in 2022, followed by a significant increase in 2023, with no significant change observed in 2024, all relative to the 2021 baseline. These short-term fluctuations could be attributed to a combination of factors, including potential observer bias, the initial effects of livestock grazing or pig rootling, or the influence of extreme weather patterns (e.g., hot conditions in 2022, dry in 2023, and very wet in 2024).

In contrast, Common Cow-wheat abundance showed no statistically significant change across the years. This stability aligns with expectations given the current low stocking rates. Ecological impacts from grazing on Common Cow-wheat may not yet be discernible due to the limited intensity and spatial scale of current grazing and browsing activity. In future years, when bison are affecting more of the site, we may start to detect longer-term changes in the abundance of these food plants.

Peak counts of Heath Fritillary declined across most sites in the Blean landscape in 2022 (Lofting, 2024). Their flight period coincided with record-breaking high temperatures, which likely imposed physiological stress on the butterflies. Extreme heat can disrupt metabolism, flight muscle performance, and feeding behavior. This stress, combined with a reduction in the availability of Ribwort Plantain and possibly other key food plants, likely contributed to the population decline in 2022.

These initial results underscore the importance of continuous monitoring to understand the responses of key floral species to the new conservation management approaches at Wilder Blean. While Ribwort Plantain exhibits sensitivity to inter-annual variability, Common Cow-wheat appears more stable. Continued long-term monitoring of both food plant and Heath Fritillary populations will be critical for adaptive management, enabling timely interventions if statistically significant changes are detected that deviate from conservation objectives.

References

Borer E & Risch A (2024). Planning for the future: Grasslands, herbivores, and nature‐based solutions. Journal of Ecology. DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.14323.

Lofting S P (2024). Heath Fritillary in the Blean 2024. Butterfly Conservation Report No. S24-06. Wareham, Dorset.

Natural England (accessed May 2025). West Blean and Thornden Woods SSSI. https://designatedsites.naturalengland.org.uk/SiteDetail.aspx?SiteCode=S1003346